I have to admit that “clause tracking” sounds good. Let’s analyze how many deals contain our preferred limitation of liability clause. Let’s track how many times we had to use fallback #2. It feels like these would be really useful things to know. Which is probably why so many contract managers ask for it.

But as you peer behind the shiny facade of clause tracking, things start to look a little grimy. To explain why, I’m going to use a real life example that I recently plucked from the EDGAR database:

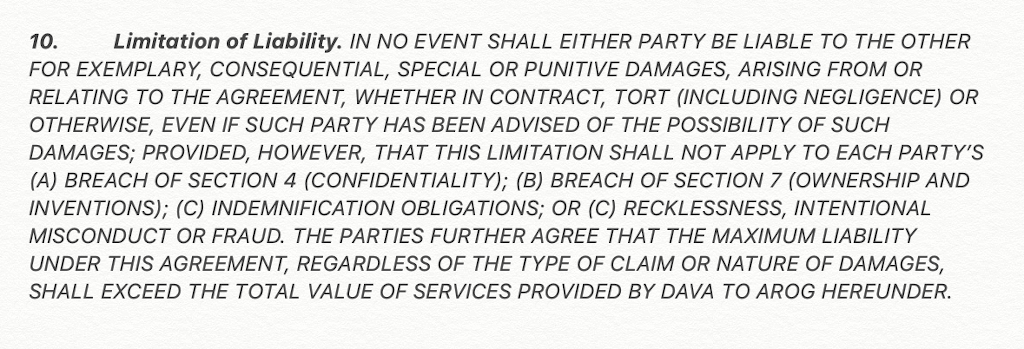

10. Limitation of Liability. IN NO EVENT SHALL EITHER PARTY BE LIABLE TO THE OTHER FOR EXEMPLARY, CONSEQUENTIAL, SPECIAL OR PUNITIVE DAMAGES, ARISING FROM OR RELATING TO THE AGREEMENT, WHETHER IN CONTRACT, TORT (INCLUDING NEGLIGENCE) OR OTHERWISE, EVEN IF SUCH PARTY HAS BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES; PROVIDED, HOWEVER, THAT THIS LIMITATION SHALL NOT APPLY TO EACH PARTY’S (A) BREACH OF SECTION 4 (CONFIDENTIALITY); (B) BREACH OF SECTION 7 (OWNERSHIP AND INVENTIONS); (C) INDEMNIFICATION OBLIGATIONS; OR (C) RECKLESSNESS, INTENTIONAL MISCONDUCT OR FRAUD. THE PARTIES FURTHER AGREE THAT THE MAXIMUM LIABILITY UNDER THIS AGREEMENT, REGARDLESS OF THE TYPE OF CLAIM OR NATURE OF DAMAGES, SHALL EXCEED THE TOTAL VALUE OF SERVICES PROVIDED BY DAVA TO AROG HEREUNDER.

The most glaring problem with this clause should be clear to an experienced contract negotiator fairly quickly. The word “NOT” is missing. Rather than saying “SHALL NOT EXCEED” it says “SHALL EXCEED”. And so what was probably intended as an aggregate cap on the supplier’s liability, instead becomes a strange declaration of liability exposure. Clearly, someone made a mistake. Quite a big one.

Which brings me to clause tracking. How do I build a machine that can spot this problem and flag it for remediation?

If my clause unit is the whole numbered paragraph 10 above (which seems reasonable on its face), then a clause tracking tool might use a statistical bag of words method to tell me that (because of the missing 3 letters) this is a 99% match to my preferred limitation of liability clause. But given the difficulty of perfectly matching in the grubby world of scanning errors, I am tempted to ignore 1% errors as immaterial. So this clause probably gets a green light.

This is the “perfect match” conundrum. In the real world of imperfect scans and OCR errors, I am almost never going to get a perfect match, so I treat 99% as OK. But in many cases, including the example above, a 99% match could actually contain a very high risk error.

If the other party produces the first draft (“third party paper”), your chances of clause matching go from bad to worse. Even if their template includes an acceptable version of the clauses you require, there’s a vanishingly small chance they used the same words as your clause library. So even the “matched” clauses will be well below 100% and you’ll have to double-check everything.

To be fair, a clause matching tool might redline the missing words and help a human negotiator to catch any mistakes. But redlining isn’t exactly ground-breaking. All it does it augment a skilled human process. We can unlock far more value by eliminating human tasks rather than augmenting them.

Another (arguably better) approach is to train a machine to understand the meaning of a “clause” and to define your risk playbook semantically, rather than by reference to precise word combinations. In this approach, you might split Section 10 into two semantic concepts. Sentence #1 is an exclusion of indirect loss, which is good. Sentence #2 is (or would be, but for the error) an aggregate cap on liability, which is also good (for the Supplier).

By training a machine with many examples of these two concepts, we can produce an AI service that assigns the correct semantic meaning to any sentence/clause processed, regardless of the precise words used. This offers far more value than precise word matching because it works not just for deals on our paper, but also for deals on third party paper.

We still need to solve the problem of training our machine to understand mistakes. Sentence #2 looks extremely similar to a liability cap. But it isn’t. So I need a “typo” training class to teach my AI that sloppy drafting like this should not be confused with the real thing.

Don’t get me wrong. There is some value to “perfect match” clause tracking if you are working with high fidelity documents that don’t suffer from OCR noise. But semantic machine learning analysis has far greater potential to automate contract review, especially if a large chunk of your deals are on third party paper.